Complete guide to computer system validation in 2025

Computer system validation continues to bring a lot of uncertainty and questions, particularly as new publications like the Second Edition of GAMP 5 guidance are rolled out.

"What does modern CSV really demand for electronic quality management system adoption?"

"What will my auditor expect to see when I show them the eQMS software we’ve been using?"

"Do we still need IQs, OQs and PQs?"

These are common and recurring questions.

We’ve assembled this guide, with the help of computerized system compliance expert Sion Wyn, to answer these questions for you.

Table of contents

- Computer system validation

- Computer system validation (CSV) to computer system assurance (CSA)

- What are regulated companies doing wrong with their computer system validation approach?

- Computer system validation: quality, not compliance

- A new approach to computer system validation for electronic quality management systems

- The Enabling Innovation Good Practice Guide

- The Second Edition of GAMP 5 guidance: what’s changed?

- Conclusion: ten key takeaways

Computer system validation

What is computer system validation?

It's the process of ensuring that the digital tools used by regulated companies are safe and fit for purpose.

After all, a bug or untested feature in a software system that helps treat patients or helps to produce drugs and devices can have a disastrous impact.

Between 1985 and 1987, the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine subjected patients to massive doses of radiation because of an undetected series of programming errors. Even now, about 24% of FDA medical device recalls are triggered by software faults.

Computer system validation, or CSV, is almost as old as computers themselves.

In 1983, the FDA's Computerized Systems in Drug Establishments, more commonly known as the 'Blue Book', was unveiled. 3 years later, the Guidelines on General Principles of Process Validation followed.

CSV validation in its most current form came in 1997 with the publication of the FDA's General Principles of Software Validation, which were tweaked and revised in 2002.

At its core, computer system validation is about answering the key question:

"Is your software system fit for use in a regulated GxP environment?"

Computer system validation (CSV) to computer system assurance (CSA)

The primary recent development in the world of computerized system compliance is the shift from computer system validation to computer system assurance.

What’s driving the shift? And what does it entail?

In a nutshell, the FDA wants life science businesses to invest in computerized systems that digitize, automate and accelerate quality and manufacturing processes.

These systems, after all, slice the risk of human error.

They free up manual admin time for continuous improvement and quality assurance work.

And they contribute to faster, safer delivery of life-saving products to patients.

But the requirements of computerized system validation, outlined in the FDA’s 1997 General Principles of Software Validation, were seen to discourage this adoption of digital tools by presenting an image of unnecessary burden to regulated companies.

Written when they were, CSV guidance had to be stretched to match the 21st-century world of CRMs, LIMs and eQMS platforms.

In the absence of updated guidance, many businesses fell back on conservative, time-consuming validation processes for fear of being non-compliant.

Some businesses gave up altogether.

Rather than going through what was perceived as a time-heavy, expensive and laborious validation process, they chose to stick with basic quality management tools like paper and spreadsheets.

After all, they require no rigorous setup and can be applied instantly. By our count, around 49% of life science companies continued to use this ingrained manual approach in 2023, particularly start-up and scale-up businesses.

The consequences of this hesitation to digitize can be profound.

Companies reliant on legacy quality tools continue to spend inordinate amounts of time on paper-pushing and battling leaky, uncontrolled information flows.

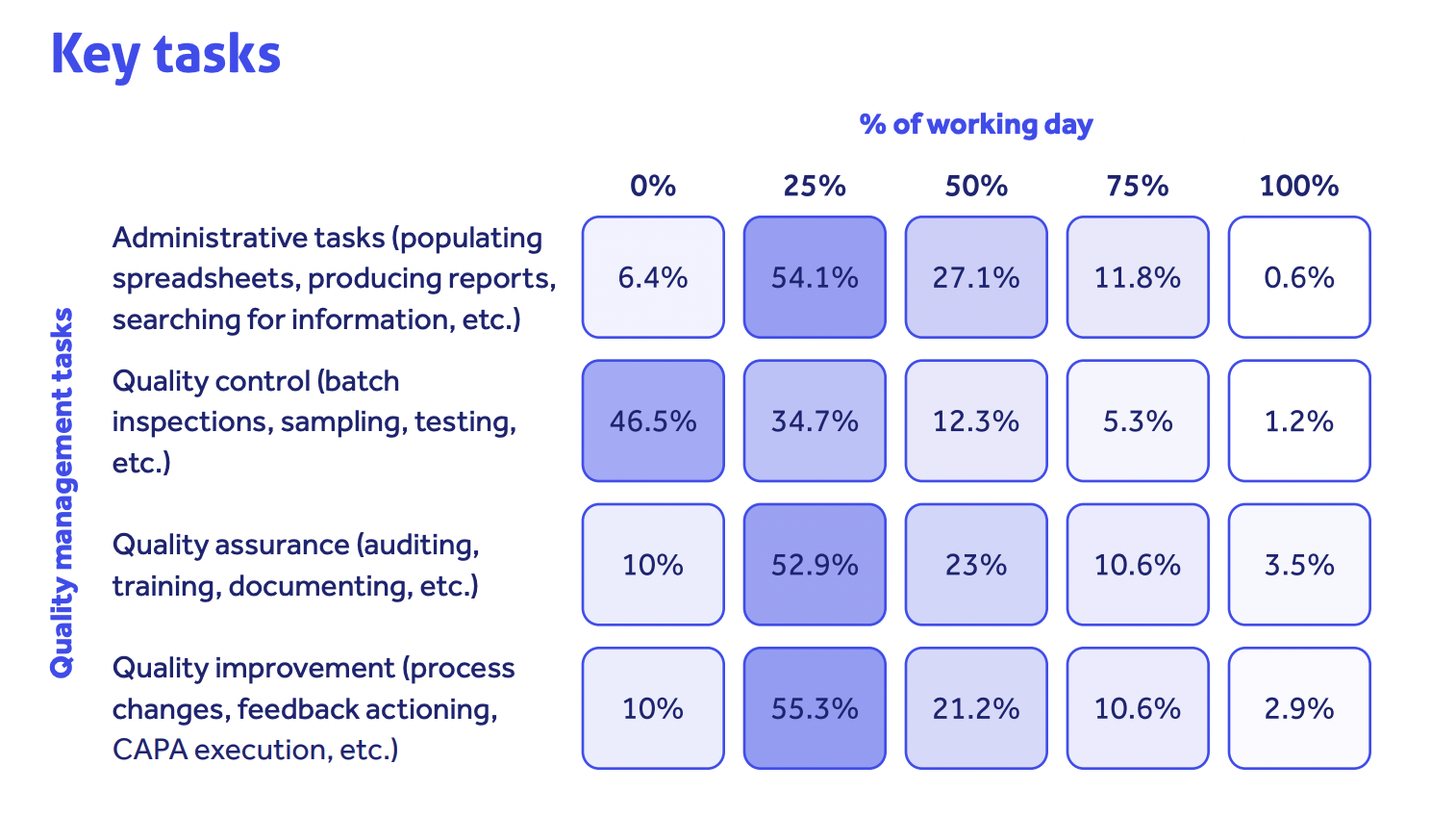

Our quality trends survey revealed that over half of life science quality professionals spend a quarter of their working day just populating spreadsheets, producing reports or searching for information.

This saps time from the real quality work of continuously improving product and patient safety. And it blocks the industry best practice outlined in GAMP 5 guidance and FDA CSV guidelines.

“Where there aren’t the tools and systems in place, there aren’t enough resources or energy to put into quality improvement.

80% of the effort should be there, but currently it’s where only 20% of time is spent.

This means we’re not focusing on the bigger picture, which is patient safety.”

- Sion Wyn

The evolution from CSV validation to CSA aims to make the adoption of compliant computerized system tools simpler, more streamlined and more straightforward.

In the FDA’s words, the ‘least burdensome approach’ is to be followed - as long as the proper care is taken to safeguard the integrity and quality of the products you make.

Instead of producing lots of documents to validate a digital system and show to auditors - who, incidentally, are only interested if there’s a direct high risk to patient safety at play - regulated companies should instead adopt an agile and risk-based assurance approach to the tools they adopt, trusting system vendors to perform their own testing activities and supplementing sensibly for high-risk areas as required.

The logic is clear:

Computerized system assurance focuses on:

-

Critical thinking and risk-based adoption of computerized tools

- Jettisoning of unnecessary legacy validation documents, like IQs, OQs and PQs

- Eliminating fear of regulatory inflexibility as a blocker to the adoption of new technology

- A return to the original ‘spirit’ of the GAMP 5 guidance:

- Proving your computerized system is fit for intended use

- Ensuring your computerized system meets the basic baseline of compliance

- Managing any residual risk to patients and to the quality of the final medicinal product

Above all, it’s important to note that CSA isn’t ‘new’ in the strictest sense of the word.

On the contrary, it’s designed to remove the perceived barriers standing between life science companies and the innovative, agile approach to computerized system adoption already outlined in GAMP 5 and its associated Good Practice Guides.

To that end, the emphasis for modern computerized system compliance falls on cultural change within regulated businesses, rather than any dramatic overhaul from the regulators themselves.

The dawn of the CSA age was formally triggered with the FDA's launch of their new draft guidelines, 'Computer Software Assurance for Production and Quality System Software', in September 2022.

Read our blog post: What do the FDA's new CSA guidelines mean?

What are regulated companies doing wrong with their computer system validation approach?

Computer system validation: quality, not compliance

The shift from computer system validation to computerized system assurance is part of a broader trend being driven by industry bodies such as the FDA and ISPE.

It’s aimed at replacing a stressful, self-inflicted straitjacket of compliance-based computerized system validation activity with measured, sensible, quality-based computerized system assurance actions.

As the Enabling Innovation Good Practice Guide puts it on page 9:

... the US FDA CDRH (Center for Devices & Radiological Health) has identified that an excessive focus on compliance rather than quality may divert resources and management attention toward meeting regulatory compliance requirements rather than adopting best quality practices...

The intended shift can be summarized as follows:

The old approach

1. Regulated business comes into existence and wants to bring a life science product to market

2. The company knows it must pass regulatory hurdles and inspections to do so

3. The company fixates on regulatory requirements and compliance needs, constructs its quality management system around these needs, and treats inspections as a stressful exam to be passed

4. Effort is spent on getting to the end goal of compliance and rigid clause-by-clause adherence.

Fear of adopting computerized systems because of the extra burden of validation means the company either sticks with paper OR generates mountains of documentation in tandem with its computer system vendor to show to inspectors, such as installation, operational and performance qualification reports (IQs, OQs & PQs) and complex risk assessments.

5. The auditor arrives and finds vast effort has been spent building validation packages for low-risk non-product computerized systems, such as an eQMS. Since there’s no direct risk to patient safety from these systems, they don’t want to waste time reviewing it. Meanwhile, high levels of paper and manual processes make it difficult to get the information they require to be confident the company is operating responsibly

6. In worse-case scenarios, the unnecessary one-size-fits-all attention given to low-risk systems has detracted from value-add activity and management of high-risk systems and processes. The auditor has plenty to note on his report!

The optimal journey

1. Regulated business comes into existence and wants to bring a life science product to market

2. The company knows it must pass regulatory hurdles and inspections to do so

3. The company focuses on optimizing quality, managing risks, and adopting tools that will strengthen the operation and unlock these objectives. Its quality management system is built around continuously improving the safety of the patient and the end product, and treats inspections as an incidental learning opportunity on the path to market

4. Effort is spent on getting to the constant stretch goal of optimal quality, integrity and patient safety, using regulatory requirements as a stepping stone.

Sensible risk-based assessment of eQMS platforms from established industry vendors means computerized system assurance can be performed quickly with minimal burden.

Rather than generating an unnecessary protective layer of compliance documentation themselves, they can lean on the vendor’s own testing activity and perform some additional testing if they feel it’s necessary

5. The auditor arrives and finds appropriate effort has been dedicated to assurance of computerized systems dependent on their risk profile.

The company has applied critical thinking, common sense and a risk-based approach to prove quality and compliance across the business. Because they’ve ditched paper, the auditor can access the data they need at the touch of a button.

The quality manager has a stress-free audit experience, perhaps with a few learning opportunities.

6. Eliminating fear-based compliance work means the auditor can detect clear value-add quality activity and strong management of high-risk systems and processes.

The auditor is confident in the safety and integrity of the product going to the end patient, and might even be able to finish the inspection earlier than planned!

“Dr Janet Woodcock, former acting commissioner at the FDA, has been saying the same thing for decades:

Don’t primarily think compliance, think quality.

Don’t think, ‘what would the FDA like?’

Think, ‘what would safeguard the patient and the efficient delivery of drugs?’

If you do that, you’ll keep them happy - rather than thinking the FDA wants you to produce all these documents so they’ll give you an easy ride on inspections.”

- Sion Wyn

A new approach to computer system validation for electronic quality management systems

The evolution to computerized system assurance impacts how regulated businesses work with eQMS market vendors.

FDA and GAMP leadership want regulated businesses to strengthen their quality approach by replacing manual paper-based systems with electronic systems.

The new landscape of CSA therefore aims to make eQMS adoption as quick and painless as possible, without businesses subjecting themselves to an unnecessary and time-consuming validation headache.

Good, appropriate CSA work with a reputable eQMS vendor should therefore include these things:

1. IQs, OQs and PQs? RIP!

Installation, operational and performance qualification activity was ‘borrowed’ into CSV from older process validation frameworks in the 1990s, as the industry scratched around for a suitable CSV approach.

They remain appropriate for simple computerized tools, where a linear process of installing, checking operation and checking performance can be performed.

But the linear nature of IQ, OQ and PQ processes no longer matches modern, non-linear software development lifecycles - and tends to produce the kind of unnecessary paper documentation that regulators don’t wish to see.

Their use in modern eQMS validation activity adds no value, and is symptomatic of the fear of regulatory punishment that the new world of CSA wants to stamp out.

“IQs, OQs and PQs are very ineffective in a typical large-scale modern software development or configuration environment… where those kinds of deliverables are just not a natural or useful part of the lifecycle.

But we still have these really strange situations where acceptance testing is performed, then an OQ is added as a kind of ‘layer’, or user acceptance testing is performed and there’s a document with ten signatures on to say that it happened.

There’s no reason you should have an IQ, OQ or PQ.”

Sion Wyn

The FDA’s General Principles recognized that IQs, OQs and PQs are largely meaningless for software developers back in 1997, and didn’t mandate them.

That remains the case in the 21st-century world of burndown charts, backlogs, regression testing, and other modern software testing activities. Automated testing tools like CircleCI and GitHub simply don’t produce IQs, OQs or PQs.

Remember: any eQMS vendor you work with doesn’t need to provide IQ, OQ or PQ documents to help you validate their system.

Your FDA inspector won’t ask to see them.

And using them means you aren’t adopting the agile critical thinking of modern CSA.

2) Smarter testing

Regulated businesses adopting an out-of-the-box eQMS in the traditional ‘compliance fear mode’ can fall into the trap of performing unnecessary system testing to try and protect themselves from a future auditor.

Work with a vendor that doesn’t encourage these activities and helps you get your system set up with minimal fuss and effort.

Typical mistakes include:

- Repeating testing activities already performed by the vendor

- Conducting tests on your own ‘instance’ of multi-tenancy software, where the results will be identical

- Testing by default whenever new software updates are rolled out

- (As we’ve seen) demanding IQs, OQs and PQs from your vendor

A reputable eQMS vendor will constantly test their software themselves, and assume the burden of the majority of assurance activity to prove their system meets your needs and intended use.

Perform your own testing only when your critical thinking approach suggests that a feature or new feature might reasonably impact product and patient safety.

Remember: a good eQMS vendor will help you drive a sensible quality and regulatory approach.

Encouraging you to perform non-value-add validation activity means they aren’t prioritizing your real operational needs - and they probably haven’t done their homework!

3) Sensible documentation

It’s okay to lean on your supplier’s provided documentation, especially if you aren’t configuring your eQMS and are using it out of the box.

Focus any of your own additional testing and documentation according to:

- The risk level of operating your eQMS in your particular environment

- Functional requirements, not what you think your auditor will expect to see

The FDA doesn’t prescribe the quantity or format of documented assurance evidence, precisely because it should be appropriate, risk-based and tailored to your specific use case.

The vast majority of the software development and testing is done as part of the eQMS vendor’s own quality management system.

That’s why, according to Sandy Hedberg of USDM Life Sciences, a robust supplier qualification is all that’s really needed for out-of-the-box systems, with extra ad hoc testing by you for any customized features.

The need for configuration specifications, traceability matrices and test plans will depend on your level of GxP risk and your level of configuration or customization, while effective evaluation of the methodology and tools of your eQMS vendor is key.

Only create assurance documents that are of real value to you. Key questions to answer if you perform your own testing are:

- What was the risk assessment?

- What did you test, and how?

- Who performed the testing, and when?

- What were the results?

- Were there any defects or deviations, and how did you deal with them?

A sensible, concise, preferably digital summary of this activity with a clear conclusion and treatment of risk will make your auditor happy - and critical thinking is the golden thread holding all this decision-making and documenting activity together.

Remember: a reputable eQMS vendor performs and documents their system’s assurance activity themselves, and should provide it to you as you go live. Use it as the core (and probably the majority) of your assurance records!

“If an eQMS supplier is relying on a lot of paper and is up to here with IQs, OQs and PQs, then my critical thinking is telling me that’s not an up-to-date supplier!”

- Sion Wyn

The Enabling Innovation Good Practice Guide

GAMP’s Enabling Innovation GPG was published in September 2021 to sit alongside the main GAMP 5 guidance.

It covers 3 key topics:

1. Agile software

Underlines the modern agile nature of software development and how GxP-regulated businesses can adopt and implement modern digital tools to strengthen themselves.

2. IT service provider management

Service providers like cloud eQMS vendors are assuming more and more responsibility for the testing and assurance of computerized tools.

As we’ve seen, this shifts the emphasis onto regulated businesses from directly performing validation tasks themselves to evaluating and assuring how IT vendors indirectly perform them on their behalf.

The GPG breaks down how regulated businesses can evaluate vendor activity, find reputable providers, and use agreements and contracts to ensure the heavy lifting is done properly by the vendor.

3. Adoption of critical thinking to support the objectives of CSA and the Case for Quality

The Guide emphasizes the importance of ditching unthinking tickbox exercises and replacing them with full subject matter expert-led understanding of your processes, data flows and risks - and how your software’s lifecycle and usage aligns.

“It's a backwards world, entrenched in paper and with resistance to adopting new tools.

SaaS can help you in your journey. You'll have a better result.

The medical device industry feels like banking 20 years ago, when everyone was allergic to cloud SaaS products because of fear and bureaucracy. But now there are neobanks, and everything's changed.

Embrace those companies leading the charge and who can provide you services you haven't had before.

It's a good change.”

— Daniel Aragao, Chief Technology Officer, InVivo Bionics

The Second Edition of GAMP 5 guidance: what’s changed?

The Second Edition of the ISPE’s GAMP 5 computer system validation guidance was released in July 2022, replacing the First Edition unveiled in 2008.

The Second Edition is right in keeping with the shift to agile risk-based adoption of computerized systems.

Read our post: The 10 key changes in the GAMP 5 Second Edition

Conclusion: ten takeaways for computer system validation in 2025

1. Make quality your operational goal for computerized system adoption, not compliance

2. Don’t waste time on unnecessary documentation like IQs, OQs and PQs

3. Your IT vendor assumes the bulk of the responsibility for assuring the quality and integrity of their systems - it’s your job to assess and qualify them

4. Use critical thinking and risk awareness as the golden thread to inform you if you need to perform extra assurance activity, in which areas, and to what extent

5. Ensure you have in-house understanding of modern computerized system adoption to help you assess and work with suppliers

6. Don’t be afraid of your auditor or inspector

7. Proving you’ve thought about the relationship of your computerized system to the safety of your product and patient is your primary objective.

Indirect systems like an eQMS do not require the same level of assurance vigor as an adverse event MDR reporting system

8. The FDA wants you to move from paper to computerized systems: it’ll only make you stronger

9. Don’t work with a vendor stuck in outdated validation activities

10. Industry guidance, from the Case for Quality to GAMP 5’s Second Edition, is remarkably consistent. Do your own reading and make yourself an expert!

Embracing computer system validation in its most modern form is your organization's pathway to a digital evolution that doesn't mean mountains of paper or weeks of effort.

To learn how Qualio uses a modern, expert-approved computer system validation approach for our eQMS software, download our validation datasheet.